Source: Shutterstock

Source: Shutterstock

On 15 November 2017, the UK Supreme Court dismissed an appeal brought by the Scotch Whisky Association and two Belgian organisations, spiritsEUROPE and Comité Européen des Entreprises Vins (‘CEEV’) against Scottish legislation introducing a minimum unit price for alcohol. A minimum unit price for alcohol is where a unit of alcohol is prohibited from being sold below a certain price i.e. a price floor. The World Health Organization’s 2010 Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol includes the establishment of minimum prices for alcohol, where applicable, in its list of policy options and interventions under the recommended target area “pricing policies”.[1]

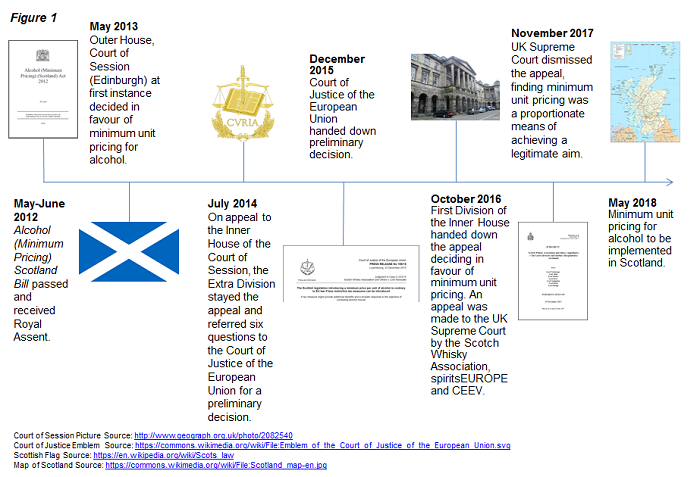

The UK Supreme Court’s decision marks the final stage of lengthy legal proceedings against the measure which was first passed by the Scottish Parliament in 2012. The Scottish Government has announced the measure will now come into effect on 1 May 2018. This blog looks at the legal challenge to Scotland’s minimum unit pricing measure and examines some of the lessons learned for countries seeking to implement such a measure.

Background to Scotland’s minimum pricing measure

The Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Bill was passed by the Scottish Parliament on 24 May 2012 and received Royal Assent on 29 June the same year. The Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 (‘the Act’) provides for Scottish Ministers to specify a minimum unit price for alcohol by order. A draft order setting the minimum unit price at 50 pence was notified to the European Commission on 25 June 2012. The Act has not yet been implemented due to the legal challenge.

Legal challenge to minimum unit pricing in Scotland

- Sequence of legal challenge:

On 15 November 2017, the UK Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the appeal, finding that minimum unit pricing is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. Figure 1 depicts the timeline of the legal challenge.

- Substance of legal dispute:

The legal challenge primarily concerned the compatibility of minimum unit pricing with EU law, specifically:

- Whether the measure, which the Parties agreed was a quantitative restriction on the importation of goods, and therefore infringed article 34 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’), could be justified under article 36 of the TFEU which provides, inter alia, that measures infringing article 34 can be justified where made for the protection of health and life and where the measure is a proportionate means of achieving this objective; and

- Whether the EU Council Regulation on the common organisation of markets in agricultural products (Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013) prohibited the imposition of minimum unit pricing for wine.

This blog examines the findings in relation to article 34 of the TFEU as to whether the measure was a quantitative restriction and whether the measure satisfied the test of proportionality under article 36 of the TFEU. The arguments arising under the EU Council Regulation No 1308/2013 were dismissed on the basis of parallel principles to those arising under article 36 of the TFEU and as such will not be examined in this blog.

- Summary of findings:

- Was the measure a quantitative restriction?

The free movement of goods is one of the fundamental principles contained in the TFEU. As such, article 34 of the TFEU prohibits quantitative restrictions on imports and all measures having equivalent effect. The Parties were in agreement throughout the legal proceedings that minimum unit pricing has an effect equivalent to a quantitative restriction on imports and trade of alcohol between EU member states contrary to article 34.[2] Minimum unit pricing interferes with the ability of low cost producers in the EU to sell below the minimum price. Introducing a minimum unit price for alcohol has the effect of hindering access to the market, thereby having an effect equivalent to a quantitative restriction.[3]

- Was minimum unit pricing a proportionate means of achieving the objective and therefore justified under article 36 of the TFEU?

The Supreme Court considered a three-stage approach to proportionality:

- Whether the means chosen were appropriate for the attainment of the objectives pursued;

- Whether it was possible to attain the objectives by measures that were less trade-restrictive of the free movement of goods; and

- Proportionality stricto sensu—whether the burden imposed by the measure was disproportionate to the benefits secured.[4]

- The objective(s) pursued by minimum pricing

It was agreed by the Parties before the Supreme Court that the legislation had, and continues to have, a two-fold objective of “reducing, in a targeted way, both the consumption of alcohol by consumers whose consumption is hazardous or harmful, and also, generally, the population’s consumption of alcohol.”[5] However, new material before the Supreme Court showed that the measure would actually achieve a narrower objective, targeting the correlation between “the health and social problems arising from extreme drinking by those in poverty in deprived communities”[6] as opposed to targeting the group of harmful and hazardous drinkers more generally. Despite this narrower objective, the Supreme Court considered the aim of the measure still fell within the scope originally advanced.[7] The Supreme Court considered that it was the “really problematic drinking” that was always the objective of the Government and the nature of this was even more clearly identified by the new material available before the Court.[8]

- Appropriateness to secure the objective?

The Parties agreed before the Supreme Court that minimum unit pricing at a rate of 50 pence per unit was an appropriate means of attaining the objective.[9]

- Less restrictive measures to achieve the same aim?

Taxation was advanced as being an alternative to a minimum unit price that could equally effectively achieve the objective of targeting problematic drinking while being less trade restrictive. Before reaching the Supreme Court, the Lord Ordinary sitting in the Outer House—with the Inner House agreeing—came to the conclusion that the alternative measure would be less effective.[10] The Supreme Court accepted two of the themes advanced by the Lord Ordinary in finding that taxation would be less effective in achieving the same aim. The first—which the Supreme Court considered to be the main point—centred on minimum unit pricing targeting cheap alcohol products by reference to their alcohol content. The legislation specifies that the minimum price of alcohol would be calculated according to the formula: minimum price per unit x strength of the alcohol x volume of the alcohol in litres x 100. Minimum unit pricing could be contrasted to increased taxation which would increase prices across the board. The Supreme Court concluded that taxation would impose an “unintended and unacceptable burden” on those whose consumption of alcohol was not a problem. The second point was that a minimum unit price was easier to understand, simpler to enforce and would be less open to absorption as supermarkets and other off-trade outlets would be prohibited from selling alcoholic drinks below the minimum price per unit of alcohol to attract business, than taxation.

- The lack of market impact analysis and proportionality stricto sensu?

In relation to the third element of the test, the Supreme Court considered three points to be important:

- The comparison between health and the market was a comparison between “essentially incomparable values”;

- It was not for a court to second-guess the value which a domestic legislator may decide to put on health; and

- Regardless of points one and two, the impact on the EU market involved “incalculables”. The precise nature and effect of implementing a minimum unit price could not be fully assessed, even by experts, until the measure was in fact introduced. In this regard the Court considered the inclusion of a sunset clause—providing that the measure would expire after a period of six years unless renewed—as relevant to the assessment of proportionality.[11]

Lord Mance, with whom the remaining judges of the Supreme Court unanimously agreed, concluded, in relation to the third stage of the proportionality test:

That minimum pricing will involve a market distortion, including of EU trade and competition, is accepted. However, I find it impossible, even if it is appropriate to undertake the exercise at all in this context, to conclude that this can or should be regarded as outweighing the health benefits which are intended by minimum pricing. [12]

Broader implications for countries considering minimum unit pricing for alcohol

Scotland’s minimum unit price for alcohol looks likely to set a number of broader implications for countries considering imposition of the measure.

- The importance of a clear and specific objective:

The legal challenge illustrates the importance of a clear and specific objective in creating a robust public health measure. Lord Ordinary, the Inner House and the Supreme Court made clear that if the objective of the measure had been a general decrease in alcohol consumption it would have easily been met by a tax increase.[13] It was the specific reference to hazardous and harmful drinkers that allowed Scotland to successfully defend the measure.

- The crucial role of evidence:

The proceedings relied heavily upon material which recognised, inter alia, that by global standards, Scotland had a very high level of alcohol with the greatest alcohol-related harm experienced by those living in the most deprived areas. New material available before the Supreme Court identified a number of facts not previously evident including that the great majority of both hazardous and harmful drinkers were not in poverty, however the hazardous and harmful drinkers that were in poverty drank more than those who were not. The Supreme Court confirmed, as the Lord Ordinary had accepted, that “poorer drinkers tend to drink cheaper alcoholic drinks than better off drinkers”.[14] The Supreme Court considered new modelling which showed that minimum unit pricing would result in the greatest reduction in consumption by hazardous and harmful drinkers who were in poverty, along with fewer deaths and hospital admissions, as being relevant to the assessment of the legislation’s objective which the Court considered now to be narrower than that initially advanced.[15]

The experimental nature of the legislation prescribing minimum unit pricing in Scotland was also a relevant factor for the assessment of proportionality. The Inner House noted the only way to test minimum unit pricing in Scotland would be to trial it.[16] The Supreme Court labelled the measure “explicitly provisional” given the inclusion of the sunset clause, and considered this to be significant in upholding the minimum pricing regime.[17]

- The importance of public health and the sovereign right of states to regulate

Article 36 of the TFEU provides for quantitative restrictions or measures having the equivalent effect to be justified where made on a number of grounds including but not limited to public morality, public policy or public security, and the protection of health and life of humans, animals or plants provided they are proportional to achieving the objective. Throughout the proceedings, it was the protection of health and life of humans that was recognised as being the most important of the article 36 protections[18] and a matter for the Member State to decide “within the limits of the Treaty, how far they wished to go in protecting health and life from harmful aspects of alcohol consumption”.[19]

The Parties were in agreement that minimum unit pricing would affect the market. The Supreme Court regarded it as a “sensible precondition” when assessing proportionality to address the impact faced by the market because of the measure. However, the Supreme Court in this case considered that it was impossible to balance the health benefits on the one hand against the detriment caused to the market on the other, as “[a]ny individual life or well-being is invaluable”[20] The Court considered that the comparison was between two “essentially incomparable values” and it was not for any court to “second-guess the value which a domestic legislator may decide to put on health.”[21]

The Court of Justice regarded minimum unit pricing not being a standalone measure as a relevant factor in determining that the legislation was appropriate to achieve the objectives. Minimum unit pricing was one of a range of 40 measures designed to “combat the devastating effects of alcohol” implemented by Scotland to reduce, “in a consistent and systematic manner” the consumption of alcohol.[22]

- Alcohol was not regarded to be like tobacco:

In a passage endorsed by the Supreme Court, the Lord Ordinary recognised that the aim of the legislation was not to “eradicate” alcohol consumption or to make the cost of alcohol prohibitive for all drinkers.[23] The Supreme Court, while not going so far as to distinguish alcohol from tobacco—the Inner House recognised that alcohol was “quite different from tobacco”[24]—considered that the imposition of taxation imposed an “unacceptable burden on sectors of the drinking population, whose drinking habits and health do not represent a significant burden”.[25]

What’s next?

Minimum unit pricing for alcohol came into effect in Scotland on 1 May 2018. Both Ireland and Wales have indicated their intention to implement minimum unit pricing for alcohol.

[1] WHO 2010 Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol, para 34(d).

[2] Outer House [28]; Court of Justice [32]; Inner House [166]; Supreme Court [3].

[3] Court of Justice [31]–[33], [46]; Inner House [166].

[4] Supreme Court [5]–[16].

[5] Supreme Court [19].

[6] Supreme Court [28].

[7] Supreme Court [18]–[28].

[8] Supreme Court [63].

[9] Supreme Court [18].

[10] Outer House [61]–[84]; Inner House [184]–[205].

[11] Supreme Court [47]–[63].

[12] Supreme Court [63].

[13] Outer House [76]–[77]; Inner House [184]; Supreme Courts [34], [37].

[14] Supreme Court [26]; Outer Huose [57]–[58].

[15] Supreme Court [19]–[28].

[16] Inner House [191], [201]–[202].

[17] Supreme Court [62]–[63].

[18] Outer House [79]; Court of Justice [35];

[19] Outer House [79]; Court of Justice [35]; Supreme Court [48], [63].

[20] Supreme Court [48].

[21] Supreme Court [18], [48], [63].

[22] Court of Justice [38]–[39].

[23] Outer House [54]; Supreme Court [24].

[24] Inner House [184].

[25] Supreme Court [63].